We analised 17 samples of late antique and early medieval pottery from a range of classes and periods from Villamagna, along with two samples from the Roman-period kiln at Olevano (Tab. 1). Thin sections were studied with a polarising microscope to identify homogeneous groupings, which might indicate single production centres or workshops, and provide data on technology and provenance, with a particular interest in determining whether there was evidence for local pottery production at Villamagna in the Roman or Medieval periods. A detailed view of the compositional characteristics and techniques used for the different samples is in Table 2. Here, we will briefly discuss the findings.

Table 2. Synthesis of the principal compositional and textual characteristics and techniques of the analysed samples.

The material is rather heterogenous, both in terms of its composition and--above all-- in the texture of the clay bodies. This is true even within the single classes investigated, suggesting that Villamagna consumed productions coming from different workshops or areas. The two control samples, from Olevano, were also different one from the other, and this fact also limited their usefulness as comparisons with Villamagna.

It is very difficult to determine the origin of the materials studied. It cannot be excluded that at least some of the products might have been made locally, but at the current state of our knowledge, it is impossible to distinguish with certainty those that were made locally from those that were regional or extra-regional.

Geological-petrographic information

Villamagna lies in an area pertaining to the internal sector of the Central Apennines. This area is characterised by the chains of the Simbuini and Hernici Mountains to the north and the Lepini Mountains to the south, which are separated by a deep tectonic depression, through which flows the river Sacco. In this area three main geological units are present: the Latium-Abruzzi sequence, the Sicilide Complex, and the Plio-Quaternary sedimentary and volcanic bodies.1 The Latium-Abruzzi sequence, which is affected by intense deformations, is characterised by a Triassic-Paleocene thick stratigraphic section of carbonate platform (limestones and dolomitic limestones) overlaid by a lower Miocene ramp and platform carbonates that are unconformably covered by a upper Miocene thick siliciclastic turbidites and calcareous and clayey sediments, and Messinian–lower Pliocene piggy-back basin deposits. The Sicilide Complex tectonically overlies the Latium-Abruzzi sequence and is composed of Cretaceous-Paleocene oceanic chaotic sedimentary bodies (mainly siliciclastic pelites and subordinately limestones). The Plio-Quaternary sedimentary and volcanic bodies unconformably overlie the Latium-Abruzzi sequence and the Sicilide Complex, are mainly concentrated along the Sacco valley, and are represented by alluvial, eluvial, colluvial, marsh and slope clastic sediments, travertines, and pyroclastic, tuff, redeposited volcanic ash deposits.2

In many of the fabrics the presence of certain distinguishing components clearly attributable to the Plio-Pleistocene K-alkaline volcanites, such as, in particular, melanitic garnet, sanidine and leucite, undoubtedly indicates that they come from Lazio or, more generally, from the Tyrrhenian area between southern Tuscany and Campania, as well as from the Vulture area. The relative proportions of these components is often low, however, which would seem to suggest that the production centres are located in marginal areas to these complexes. Other samples have more generic inclusions that would seem to exclude a provenance from volcanic areas. However, we should take into account that if some of the productions were carried out with local sediments coming from deposits that preceded the Plio-Pleistocene events, the fabrics would in any case lack volcanic components.

A fact to note is the widespread presence, almost always dominant over other components, of fragments of quartz-feldspathic and acidic metamorphic rocks (quartzschists, quartzmicaschists, in some cases even gneisses) and/or isolated minerals (quartz, feldspars, micas; the latter much more frequent, especially quartz) derived from these rocks. Acidic metamophites or granites do not outcrop either locally, nor in the other volcanic areas of Lazio and Campania, while they are present in Tuscany and in other more distant basement areas (for instance in the Alps and the Calabro-Peloritan area). Elements derived from granitic and metamorphic rocks are found, however, in secondary deposition in many Messinian-lower Pliocene sedimentary rocks in the central Apennines, even in areas hundreds of kilometres far from the basement rock outcrops.3 (Clasts of granites and porphyries are also reported in upper Miocene conglomerates outcropping in the territory of Anagni, although not in the immediate vicinity of Villamagna.4) The percentages and the size of the fragments of metamorphic rocks in the fabrics of the ceramics studied, never high, might as well suggest their origin from sandstones, which, on the other hand, can be observed in small quantities in some samples.

Even if the fabrics studied are quite variable, the peculiar dominance of quartz and acidic metamorphic components (frequently associated with rare volcanic elements) in many samples of various typology and chronology might point to the existence of a main source area, not very far from Villamagna, where several production sites were scattered in space and time. On the other hand, the analysis of the geological cartography and the available bibliography apparently do not support the hypothesis of local or subregional productions. Therefore, in order to verify the possibility that the metamorphic inclusions indicate provenance from the surroundings of Villamagna one would need to survey the area and sample the raw materials available, looking for such components in the sandstone clasts or the alluvial sands of the local streams, whose origins lie further north.

Such a survey would also verify another secondary element apparently contrasting with the possibility of the presence of local pottery production. Limestones are very common in the area, but the fabrics possibly deriving from alluvial deposits are entirely without calcareous inclusions or fragments of carbonate rock. The accessory clasts of cherts (and radiolarian cherts) could be related not only to the carbonate sequences, but also derive from the reworking of Apennine sandstones, where this component is associated with quartz-feldspar clasts.

Integrating the archaeological data

Considering their texture and techniques, and secondly, petrographic composition, the seventeen samples can be grouped into six major groups, with some variability within them.

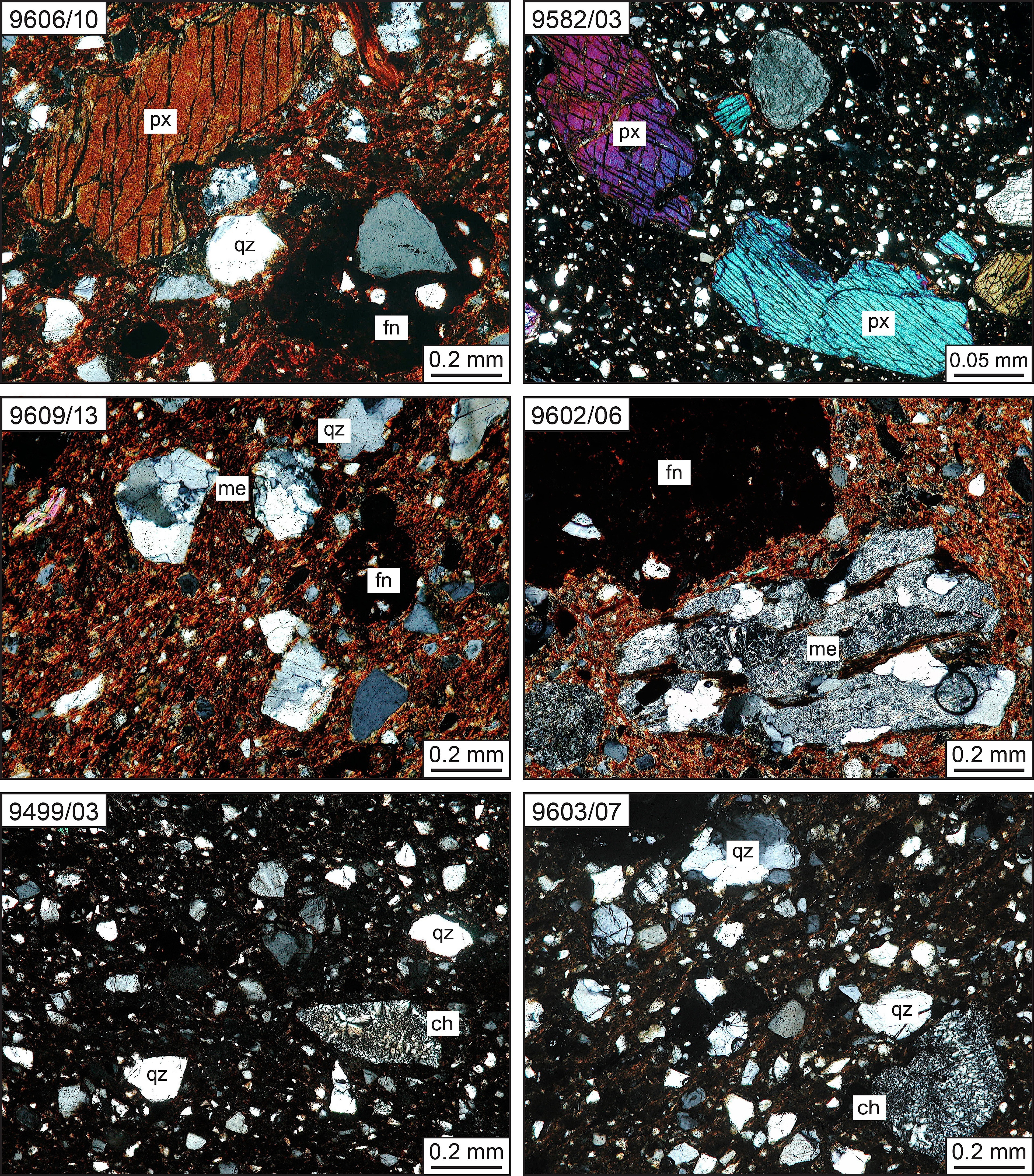

- Two cooking ware fabrics (9606/10 and 9607/11) and one of the samples from the kiln site at Olevano (9582/3) have coarse inclusions (Fig. 1, top), probably added to ferric alluvial clay, itself rich in inclusions essentially of acidic metamorphic origin. In the first two fabrics the coarser fraction is both metamorphic and volcanic in composition, while in the third the clasts have an exclusively effusive source. The only possible link between the three samples is constituted by the clinopyroxenes, with similar characteristics.

- In the remaining cooking wares (9608/12 and 9609/13), a late antique sample (9581/2), a globular amphora (9602/6) and a Roman sherd (9580/1) silty inclusions are generally abundant and the coarser fraction is moderately abundant, well-sorted, medium-fine, and perhaps intentionally added. It consists mainly of grains of quartz, feldspar and subordinate fragments of metamorphites, while mica is rare (Fig. 1, middle). The volcanic component is present in all of the samples, very poor in the medieval samples (mainly mineral individuals), and relatively more abundant in Roman samples, where there are several fragments of leucite-bearing lava.

- The fabrics of the two samples of Forum Ware (9499/3 e 9500/4 and one of the globular amphorae (9603/7) are characterised by very abundant poorly sorted inclusions (Fig. 1, bottom). In this case, too, they are constituted mainly by quartz, but the volcanic component is apparently absent in all of the samples.

- The sparse-glazed sherd (9605/9), a globular amphora (9601/5) (Fig. 2, top right) and one of the Roman samples from the Olevano kiln (9583/4) (Fig. 2, centre left) present rather different fabrics, but all of them characterised by fine, poorly sorted inclusions, constituted in the main by quartz, associated with numerous micas. The volcanic component is rare. For this group, the use of unmodified alluvial clay is likely.

- The second two samples of Forum Ware (9497/1 e 9498/2) are distinguished by a very ‘pure’ matrix with a scarse silty component and numerous rather coarse but well-sorted sandy inclusions (Fig. 2, centre right). The latter, mainly composed of acidic metamorphic elements (quartz prevailing on feldspar and schist fragments), associated with scarce volcanic elements and cherts, should probably be interpreted as a temper, possibly of alluvial origin.

- The three fragments of unglazed fine wares (9604/8, 9610/14 and 9611/1) constitute a very separate group from the rest, insofar as the fabrics are constituted by a carbonate rather than ferric matrix and by rare, fine inclusions, among which calcareous microfossils (Fig. 2, bottom). It is probable that, in this case, the raw materials come from unmodified marine (or lacustrine) sediments. Only sample 9611 shows some rare volcanic elements (leucite-bearing lavas).

As for the two kiln wasters from Olevano, it must be stressed that their fabrics are very different one from the other and none of them presents striking similarities with the samples from Villamagna. However, the abundant clinopyroxene that characterises the temper of 9582/3 shows relatively peculiar (also macroscopical) features and seems similar to the clinopyroxene inclusions that can be observed, scarce or very rare, in the samples 9605/9, 9606/10, 9607/11, 9608/12, as well as in 9583/4.

Further discussion of the materials from Villamagna can be carried out considering the individual pottery types studied.

Forum Ware (Vetrina pesante)

9497/1 (Fig. 2 centre right) and 9498/2, characterised by rather distinct fabrics for their composition and technique, can be attributed to Sfrecola’s group 9c.5 The presence of volcanic inclusions, even if in small quantities, is compatible with the distribution of the type in Rome and Lazio. However, a southern Tuscan provenance would be even more congruent petrographically, given the dominance of acidic metamorphic components. These latter exclude a Campanian origin. The two samples differ essentially for their firing conditions: reducing in the one case and oxidizing in the second, which created the macroscopic colour differences in the fabrics, respectively grey and red. The yellow-green colour of the glaze probably comes from the presence of iron (possibly a result of the use of impure quartz-rich raw materials). The glaze on these samples is rather bubbly, thick and irregular (9497/1: 0.1–0.5 mm, 9498/2: 0.1–0.3 mm), which seems to indicate a single firing.

The other two samples, 9499/3 (Fig. 1, bottom left) and 9500/4, are relatively similar and clearly different from the last, especially in terms of their textures and the technical characteristics of their fabrics. Their composition is relatively generic and the absence of a volcanic component would exclude the hypothesis of a local or even regional origin. A broad apenninic provenance is possible, but the lack of diagnostic inclusions does not allow us to provide precise provenance indications. The glazes are equally yellow-green in thin section, but very thin, around 0.2 mm, and less irregular than in the case of samples 9497 and 9498. In this case, a second firing cannot be excluded.

Sparse Glaze (Vetrina Sparsa)

The sample 9605/9 (Fig. 2, upper left) reveals a red oxidised matrix only on the unglazed side, while the rest of the fabric was fired in the total absence of oxygen. The fabric is rather similar to those of 9499/3 and 9500/4, but is distinguished by the abundance of mica and the presence of a volcanic component (clinopyroxene and melanitic garnet). The latter, though rare, suggests a local or regional provenance. The glaze, whose green colour is probably due to the presence of unoxidised iron, is thin, but rather regular, around 0.1 mm thick.

Globular Amphorae

The three samples 9601/5 (Fig. 2, upper right), 9602/6 (Fig. 1, centre right) and 9603/7 (Fig. 1, bottom right) are related in their shared characteristic of dominant elements derived from acidic metamorphites associated with rare volcanic and chert inclusions. However, they are quite different one from the other and were probably made in different centres or workshops. The infrequent volcanic inclusions in these are not specific to the Tyrrhenian and could come from other areas dominated by metamorphic rocks. While we cannot exclude that these were local, it seems nonetheless unlikely; it seems impossible that might have come from the area of the Bay of Naples.

Common wares

The samples 9604/8, 9610/14 and 9611/15 (Fig. 2) are different from all of the others, in that they are primarily made with carbonatic materials which were refined, probably originally so. 9604/8 and 9610/14, partially similar, have a rather ‘pure’ matrix and few inclusions, principally made up of microfossils (unidentifiable foraminifera, rare fragments of bivalve shells) and the exterior is slightly whitened. Even if carbonatic sediments are present near Villamagna, the fabrics are very generic and they might have come from many other parts of central and southern Italy. 9611 is noticeably different for its firing conditions; a neat reddened band, significantly more oxidised than the rest, is visible near the surface. It also has greater frequency of silicate inclusions and a few volcanic components, which suggest a local or regional provenience.

Cook wares

9606/10 (Fig. 1, upper left) and 9607/11 are partially comparable. They are different one from the other in the percentages of the different granulometric fractions. Both have abundant, also coarse-grained (added) inclusions, mainly consisting of metamorphic and volcanic elements (clinopyroxene dominates over melanitic garnet and leucitic lava). There are also few cherts and numerous iron-rich (limonitic) nodules.

9608/12 and 9609/13 (Fig. 1, centre left) are, by contrast, characterised by medium-fine inclusions, mostly composed of quartz. They are more abundant, especially the silty fraction, in 9608/12. The volcanic inclusions are very rare: sanidine in 9609/13, relatively large clinopyroxene in 9608. 9608 is different with respect to the others also for the higher firing temperature and the neat (red) oxidised exterior surface, which is clearly differentiated from the non-oxidised grey brown nucleus. The volcanic component points to a local (especially in the case of 9606/10 and 9607/11) or regional production for all the samples.

Roman pottery

The 2 samples 9580 (fabric Coarse Ware 4) and 9581 (fabric Coarse Ware 3) are partly comparable. They have well-oxidised iron-rich matrix and moderately well-sorted inclusions, essentially medium-fine, which are principally composed of quartz and other acidic metamorphic elements. 9580 has a greater frequency of fine inclusions and many fragments of leucitic lavas, which are absent in 9581. The presence of volcanic components, though subordinate, makes it likely that these are both local or regional productions.

1 Alberti et al. 1975; Servizio Geologico d’Italia 1975; Sani et al. 2004.

2 Alberti et al. 1975; Sani et al. 2004.

3 Accordi and Carbone 1988.

4 Servizio Geologico d’Italia 1975: f. 389 (Anagni).

5 Sfrecola 1992: 579.