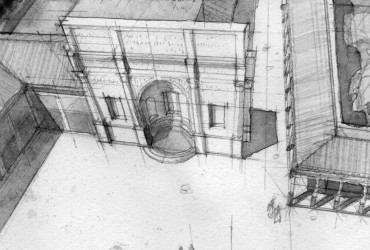

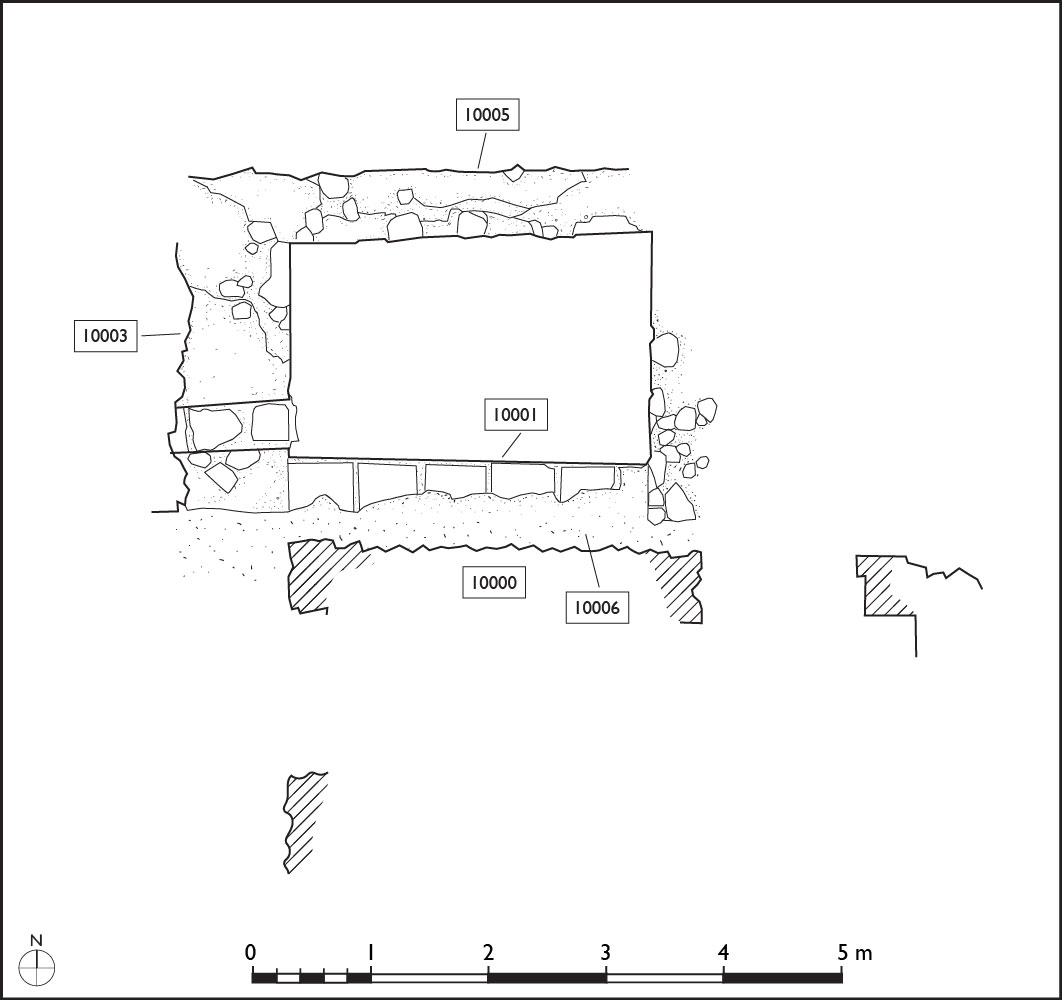

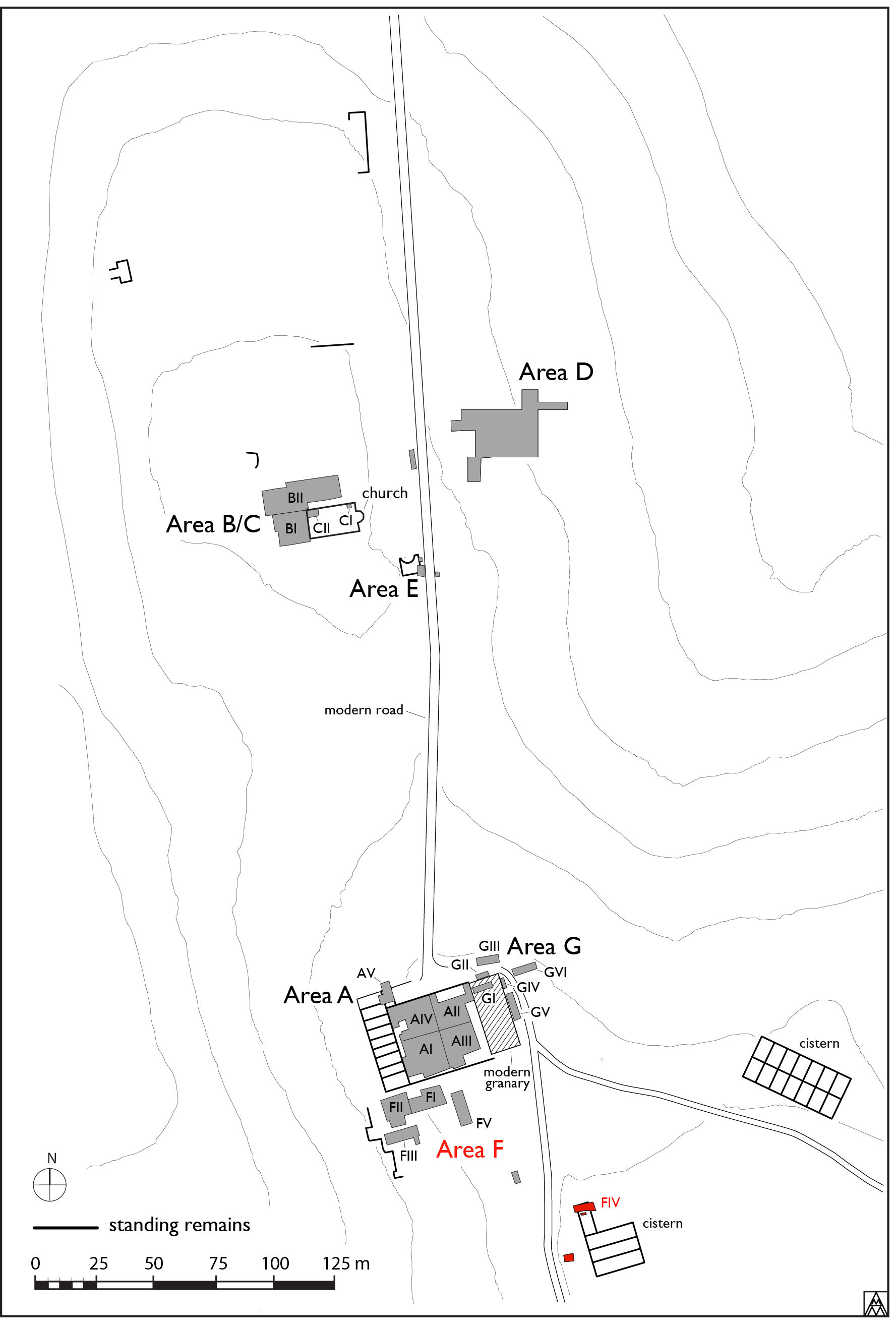

Excavation of Area FIV, the area involving the cisterns, recommenced on June 7, 2010 (Figs. 1, 2). Due to complications with the proprietor, the interior of cistern [10000], located southeast of the casale, could not immediately be excavated. Instead, the zone directly south of the cistern was explored. The area was very overgrown and impenetrable; therefore, a great deal of vegetation had to be removed. Once enough of the underbrush had been eliminated, excavation began. The remainder of the western wall [10029] of the cistern was identified, although not fully excavated. Initially it seemed that the western face of the wall formed another vault, but further investigation demonstrated that this was not the case. Exposing this wall provided a clearer understanding of the relationship between cistern [10000] and the wall [10030] that divides it into two separate chambers (Fig. 3). Mazzolani (1969) published a drawing of the cistern [10000] that illustrates the two chambers as disjointed, however, it was demonstrated that the walls and the chamber were actually continuous and that the “dividing” wall was from a much later date.1

An attempt was also made to understand the southern wall [10031] of cistern [10000]. The southwest corner was still largely intact and it was noted that wall [10031] formed a vault on its southern face. The remains of this southern wall were excavated to the west of wall [10029] in order to determine both if a cistern existed west of cistern [10000] and if wall [10031] formed the northern wall of east–west oriented cistern [10032]. No evidence was found for another cistern to the west of cistern [10000]. Wall [10031], the southern wall of cistern [10000], was determined to continue west, forming the northern wall of cistern [10032]. The wall was largely destroyed, with only its opus incertum core remaining (Fig. 4) and the western corner of the cistern could not be identified. The corner was likely destroyed by the construction of the staircase leading to the small modern house that is now no longer occupied (Fig. 5). Although still heavily overgrown, the western wall of cistern [10032] in opus reticulatum was extant and was found to continue south, forming the western walls of cisterns [10033] and [10034]. No other walls of cistern [10032] are presently visible.

The remaining area of the southwest corner of cistern [10033] leads into a segment of the southern wall and the spring of the vault. The entire central portion of the vault is not visible, although it may exist underneath the vegetation. The eastern end of the cistern is still extant, along with a portion of the vault underneath the small modern house; the house incorporated the eastern vault into its structure. The eastern wall is in opus reticulatum, while the north wall, south wall and vault are in opus incertum. The base was not excavated due to time constraints and the presence of asbestos waste. The southern wall of cistern [10033] also formed the northern wall and vault springing of cistern [10034] where it remained extant.

Cistern [10034] was intact at both the east and west ends (Fig. 6), while the central portion of the vault had collapsed. The construction method of the walls of this cistern is the same as that of the other cisterns. The base of the cistern was not excavated at either end and the eastern end is mostly inaccessible due to heavy vegetation and fill. Masonry was noticed where the southern wall of cistern [10034] would have been present, along with a mound, suggesting that perhaps another cistern existed to the south. Excavation revealed, instead, that the mound was composed of very dense clean clay. The masonry proved to be a wall [10035] with a top surface that slanted from north to south (Fig. 7). The surface was covered with a 2 cm layer of cocciopesto and continued under the clay to the east, west and south. The density of the clay made its removal very slow and the surface was not fully excavated. Initially it was thought that this surface could have formed a sort of basin that functioned as part of the water supply system for the cisterns. A more likely conclusion is that the masonry forms the southern wall of cistern [10034] and that the cocciopesto was used to cover and protect the entire outer surface of the vault.

Once digging was permitted on all areas of the site, the focus of the excavation shifted inside cistern [10000], since it was determined that continuing the excavation in the trench started in 2009 would be the easiest way to find the base of at least one of the cisterns. The trench was expanded both to the south and to the east and west against wall [10028]. A pavement 10011 of horizontally laid paving stones and cement, found to slope from south to north throughout the present surface of the cistern, was determined to be modern. Excavation of fill (10008) continued below. The fill contained medium stones and the soil was very dark and clayey. Stratum 10012 sloped from south to north, forming a pavement of carefully placed small stones with traces of charcoal. Animal bones and pottery fragments (including Banda Rossa) that appeared to be burned were found below the pavement, along with marble fragments, hunks of cocciopesto, oyster shells and cubilia.

Two similar strata were found with the removal of stratum 10012: (10013), located in the eastern half of the trench and (10015), located in the western half of the trench. Both strata contained a heavy concentration of stones and blue mortar, which can likely be identified as collapsed material from the structure of the cistern. (10015) was considerably more friable and also contained pottery fragments and oyster shells. Below these two strata was a layer of very sticky dark brown compact clay (10016). Inclusions of small stones, charcoal, marble fragments, tile, cocciopesto, mortar, nails and several very large bones (horse/mule and cow) were found. The stratum also contained reddish-orange inclusions that may suggest a heavy presence of iron in the soil. The layer continued to get wetter as it was excavated down and fewer inclusions were found.

Excavation of stratum (10016) was not completed in one day and, the next morning, the base of the trench was almost completely covered with a layer of water (Fig. 8). Extraction of the clay was less difficult as a result of the water and it could be removed more quickly. As clay was taken away from directly in front of the central slit for the fistulae 10027, cold clean water gushed out (Fig. 9). It was also possible to reach down into the hole filled with water and feel a piece of lead on the edge of the hole. The hole was measured to descend for at least another 70 cm. The same thing happened when the clay in front of the slit to the west 10026 was removed, although the hole was not completely exposed (Fig. 10). Excavation of this stratum ceased at this point and it was evident that the vertical slits had in fact once held fistulae.

After a pile of stones was removed from the door opening in the western wall [10029] of cistern [10000], the trench was expanded under the pavement 10011 to the east and west, directly against the wall of the cistern [10028], to reveal stratum (10024) (Fig. 11). The stratum was explored to the west in order to certify that there was another slit for fistulae in the western corner of the cistern. The trapezoidal depression was confirmed 10025 and more broken sections of wall with impressions of fistulae were fortuitously found. One wall section, although broken, was still held together by soil; this made it possible for the full diameter and perimeter of the two fistulae to be measured, confirming that the two pipes were set up adjacent to one another and that they were of different sizes. To the east of the trench, about 10 cm of stratum (10024) was very briefly examined in order to confirm that a fourth fistulae slit existed. The presence of this trapezoidal depression enforced the likelihood that a fifth one also existed in the eastern most corner of the cistern.

In order to be sure that there was not another cistern to the east of cistern [10000], a trench was excavated with the bobcat along the eastern wall of the cistern. The stratum that was uncovered (10014) was composed of compact yellow clay and contained no evidence to suggest the presence of another cistern. Furthermore, to confirm that there was not another cistern to the west of cistern [10000] and to examine the possibility that the pipes were exiting the cistern through an opening in the damaged western wall, a trench was excavated with the bobcat along the western wall of the cistern in front of the door. No evidence of another cistern was found. The full edge of the western wall of cistern [10000] was exposed, along with what was interpreted as a cut forming a channel. The channel 10036, which may have housed fistulae, descended directly to the west under the modern road; it also branched off next to the wall, to head due north 10037 under the slanted tile described above as part of wall [10003] (Fig. 12). This tile may have formed half of a capuccina covering (10038) for a conduit to house fistulae, although this cannot be confirmed without further excavation of the area.

The source of the water supply for this cistern complex still remained to be identified. As discussed earlier, Mazzolani (1969) claimed that an aqueduct had existed along the western edge of the road. A trench was opened with the bobcat to the west of the modern road in order to investigate this possibility. The first layer of humus (10017) was removed to reveal a layer 10018 of stone, tile and lime in the center of the trench that was interpreted as a working surface. Towards the eastern end of the trench, a cut 10019 was located for the construction of a small rectangular north–south oriented wall [10020], which was composed of medium and small stones and bonded with friable mortar. Towards the western end of the trench, another cut 10021 was located for the construction of a wall [10022]. This north–south oriented wall was composed of stones, tiles and friable mortar. These two cuts cut a layer of greenish clay below stratum 10018, which contained small stones and fragments of tile. The stratum was interpreted as a natural layer of clay accumulation. The purpose of the small walls was not conclusively determined.

1 See: Miliaresis, print volume: 69–73.

![Figure 3. Wall [10030], dividing the cistern into two chambers](http://archaeologydata.brown.edu/villamagna/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Figure-3-150x150.jpg)

![Figure 4. The continuation of wall [10031].](http://archaeologydata.brown.edu/villamagna/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Figure-4-150x150.jpg)

![Figure 7. Wall [10035].](http://archaeologydata.brown.edu/villamagna/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Figure-7-150x150.jpg)

![Figure 6. West end of cistern [10034].](http://archaeologydata.brown.edu/villamagna/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Figure-6-150x150.jpg)