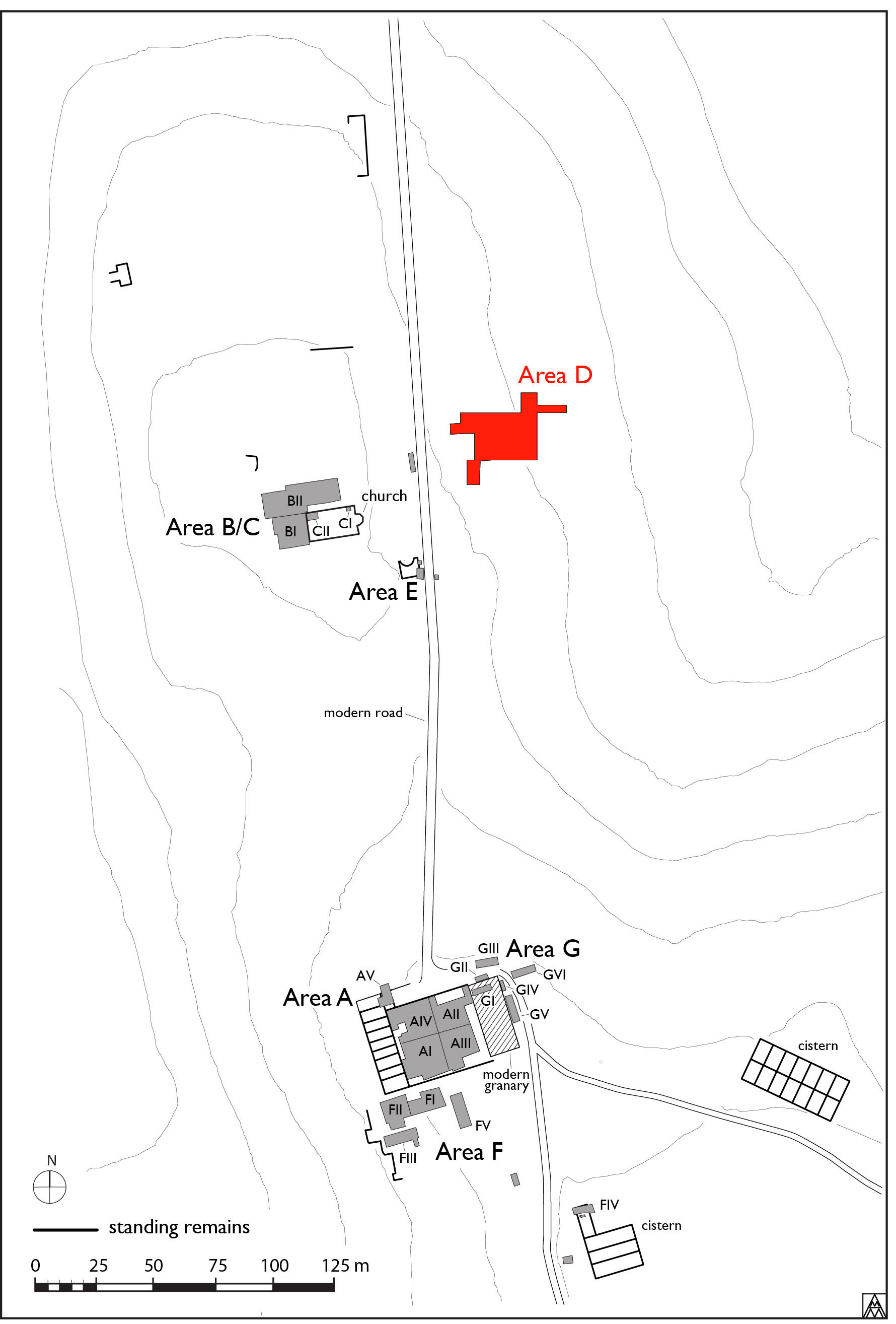

The collapse of the barracks in the 5th c. does not seem to have completely destroyed the structure. After approximately 80 years of abandonment, many parts of the structure were reoccupied in the middle of the sixth century, while a new large rectangular building, apparently serving a productive function, was built on top of its western end. This phase of activity continued until a destruction event in the middle of the seventh century. Occupation nonetheless continued at a much smaller scale. A large ditch, perhaps defensive, was cut across the site, while a series of postholes indicates the presence of huts or longhouses in the early medieval period. Finally, scant traces of activity, unfortunately too ambiguous to characterize, are evident in the later medieval period.

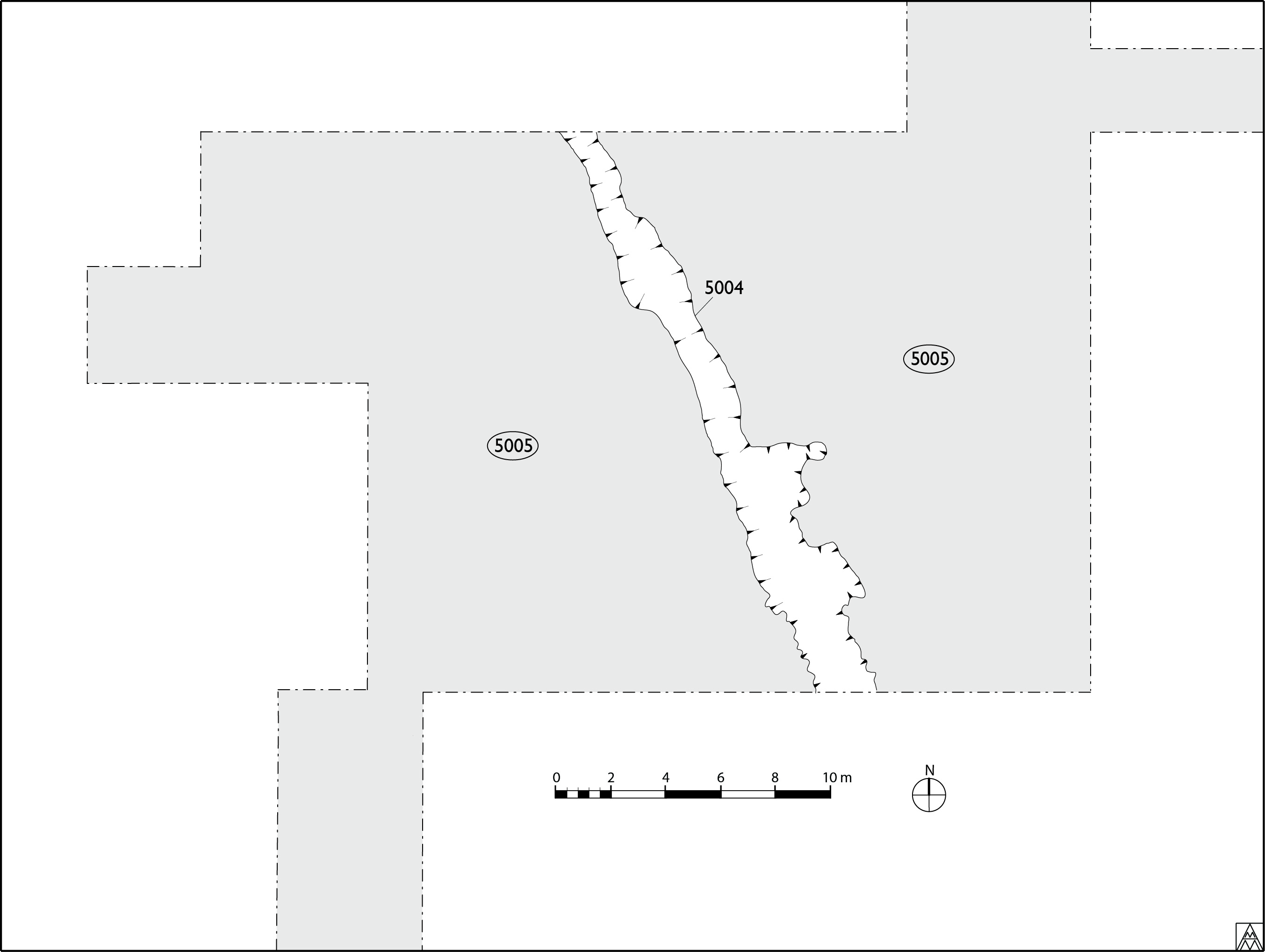

Phase V: Reoccupation (6th/7th centuries)

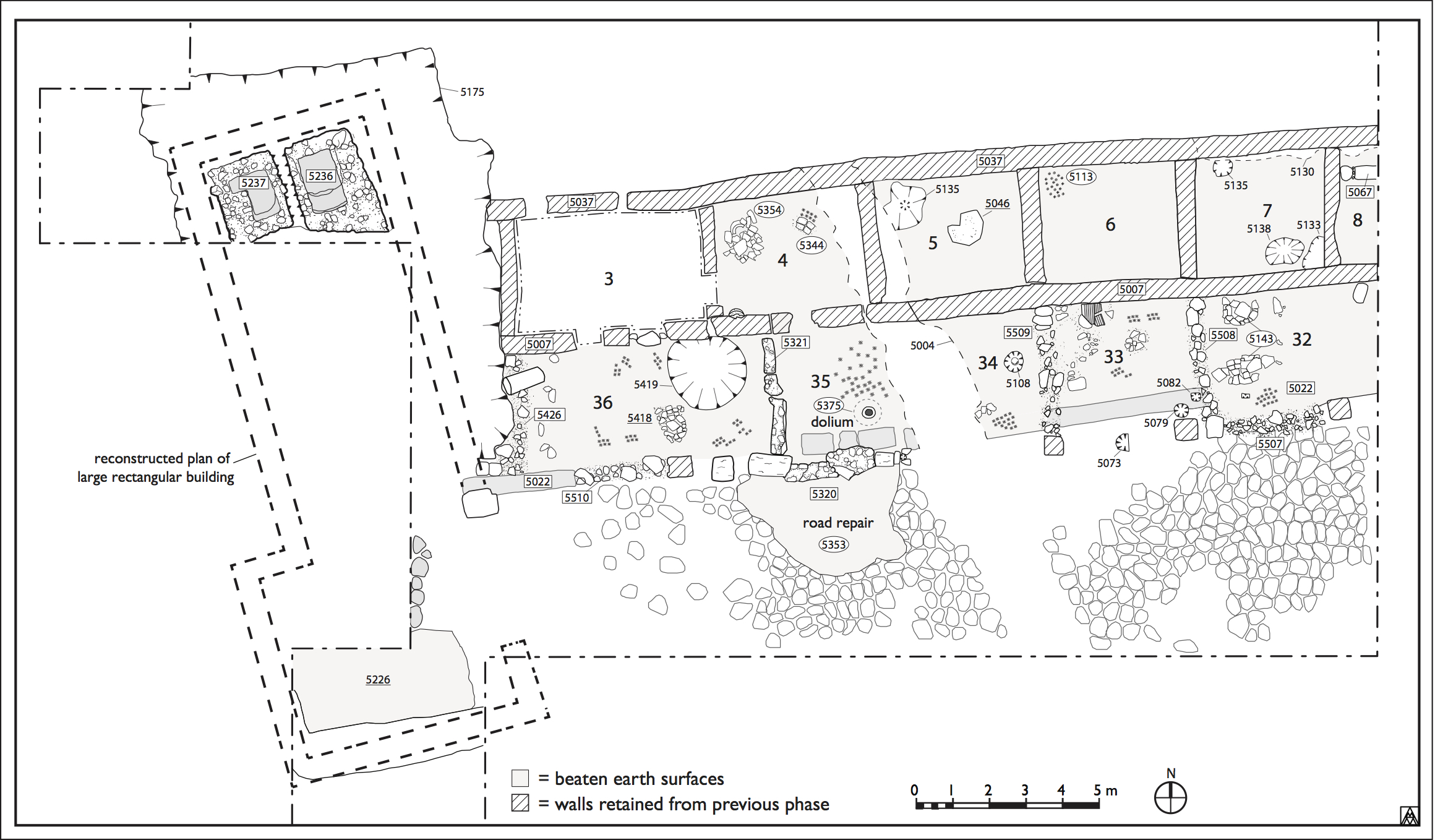

Figure 2. Plan of structure in the phase of its reoccupation during the 6th and 7th centuries (Margaret Andrews).

Approximately 80 years after the destruction of the barracks at some point the third quarter of the fifth century, occupation on the site returned in the mid-sixth century, as evidenced by the construction of new spaces with the rubble of the original structure and a particular density of material within them dating to ca. 530–650 (Fig. 2). As the reoccupied areas respect the division of spaces in the original structure, enough of it must have been standing to serve as a suitable and enticing location to (re)erect a small group of rooms.

Portico

The most dramatic evidence of this reoccupation phase was found in the space of the former portico (Room 2), which naturally would have contained less destruction debris than the main structure and offered southern exposure along the road. In cleaning out the portico for reoccupation, debris from the original structure seems to have been removed via cut 5430 as far west as the area south of Room 3. This action apparently cut down into the original surface as well, making the reoccupied surface lower than that of the original one, as the later surface lay below the top of the foundations for the portico wall to the north and well below the level of the paving stones on the road to the south. Indeed, the top of [5022], the earliest wall in the trench that had been cut and covered already for the original construction of the portico and paved road, was also exposed, and the reoccupied surface was made essentially level with it (Fig. 3).

In the cleared space, a series of rooms was newly constructed between the piers and the portico wall [5007]. These were all constructed at different levels extending up the slope of the hill (see Fig. 2). Three walls were apparent near the eastern limit of excavation, where a small room, designated Room 32, was constructed between piers [5083] and [5080]. The southern wall of this room was constructed between these two elements, which must have been at least partially intact, and thin walls built between each pier and portico wall formed the eastern and western limits. The walls were all constructed very poorly, with rubble of reused bricks, marble fragments and large mortar chunks reused from the collapsed original structure. These elements were usually bonded by a very friable lime-and-sand mortar, but occasionally only by mud and clay. The southern wall [5507] between the two piers was clearly distinguishable by the reused paving stones and large stones bonded in a bright lime-and-sand mortar. Its preserved height was constructed against the pavers of the road, which offered additional support at its base. The western wall [5508] also consisted of reused paving stones and large chunks of masonry from the original structure in a lime-and-sand mortar. It was positioned just east of pier [5080], which may not have been visible any longer, but it seems more likely that the more eastern location was meant to take advantage of a step cut into the elevation of the early wall [5022] during the original construction of the portico.1Supporting the wall on the exterior of its base, the step provided additional stability in the same way that the road and its preparation helped stabilize the southern wall [5507] (Fig. 4).

On the occupation surface 5020 of the room, two patches of what appears to have been a pavement or at least a preparation for one (5143) were found apparently in situ. These were composed of relatively large reused tile fragments pressed into a lime mortar bed, and rubefaction around them may indicate that they were used as hearths (Fig. 5). To the south of these patches, a small (10 x15 cm) rectangular hole 5112 was cut into the section of [5022] that was exposed within the room. What it housed or what function it served remains unknown.

Evidence for the presence of another thin wall [5509] was found farther west between the portico wall and pier [5032], creating the space designated Room 33, between it and [5508]. Two reused paving stones and marble slabs were arranged in a line across the surface of the portico, but little remained of the elevation. Several large pieces of a fluted marble pilaster and other architectural elements (5142) were found along the center of the northern wall. These probably had been included in the construction of [5509], which collapsed downhill. Three postholes (5073, 5079 and 5082) cut into or near [5022] may have held posts for a wooden door or fence that divided the space of the room from the road (Fig. 6).

The area to the west of Room 33, between wall [5509] and the later ditch 5004, was defined as Room 34. In the middle of it a large posthole 5108 was found, whose fill (5107) contained charred bones, charred wheat and a charred grape seed. The southern side of the cut preserved small stones and mortar, apparently intended to support the post (Fig. 5). Since no traces of a wall along the southern side of the portico were found within Rooms 33 or 34, these spaces were either open to the south or enclosed only by wooden elements; the presence of the postholes along [5022] may suggest the latter. Wall [5009] would then have served as a party wall between the two rooms.

Another newly-built structure (Room 35) was located to the west of ditch 5004. This structure was much better preserved than the eastern rooms, as it was essentially built against and protected by the rising slope to its west. It offers the clearest indication of how the entire series of spaces appeared before they burned down.

The southern wall [5320] was made of reused stones and brick fragments from the original structure. As with the southern wall of Room 32 in the east, it was constructed along the line of [5022] and atop the pavers of the road. Interestingly, the stones and bricks were arranged in courses, albeit rough, creating the appearance of an opus listatum wall resembling those of the original structure (Fig. 7). The eastern support for this wall was the tartara pier [5393] and its base, which had survived to nearly 70 cm in height. A small posthole 5413 was cut on the eastern end of [5320], just south of wall [5022], with four small fragments of reused materials placed around the cut to help support the post that it likely once contained (Fig. 6).

Southern wall [5320] seems to have originally had an opening or entrance that was filled in with rubble [5371] at a later point. This infill contained a significant number of marble elements and was not coursed like the original construction. On the southern side of the wall, a mostly intact column base was set to the south (i.e. in front) of the eastern pier, replacing a missing paving stone. On the western side, there was a small rectangular protrusion of masonry, of the same materials as that of [5230] and keyed into its base. The function of these elements remains unknown since they lay under the infill of the road, but they may have served as additional supports at the corners or perhaps as crude pilasters.

The western wall [5321] survived to a height of approximately 70 cm, and it too consisted of roughly coursed reused stones and bricks (Fig. 8). A significant amount of this wall, however, was comprised of large, reused masonry chunks, up to a meter in length and still bonded with as many as four or five courses. Two of these fragments had toppled into the interior space of the room in the SW corner, and a third had fallen to the eastern side of the wall. Still intact but clearly burned on one of these fallen fragments were patches of painted plaster consisting of a white background with red lines that had been part of the decoration of the original barracks (Fig. 9). As with Room 32 in the east, this western wall did not stretch between a pier and the portico wall, but rather was placed about a meter to the east of pier [5467]. Accordingly, the SW corner of the room was constructed with a large, rectangular tartara block. The dimensions of this block exceeded those of the portico piers, so the nature of its use in the original building remains unknown.

No eastern wall for the room was evident, and it seems unlikely that one was originally built between the base of pier [5393] and the wall. A large dolium (5375) was inserted (cut 5376) into the floor between them at the eastern limit of the southern wall [5320], and its presence seems to preclude the construction of a wall here (Fig. 10). It remains possible, even likely, that another N–S wall was constructed slightly east of the pier, but that it was subsequently removed when the ditch 5004 was cut in. The presence of posthole 5413, however, seems to suggest that a wooden gate somehow enclosed the space. It may have either stretched N–S, between [5022] and the northern portico wall [5007], closing off Room 34 from Room 35; or it may have stretched E–W along the southern limit of the portico within the area of Room 34, unifying Rooms 34 and 35 as a single space behind it. Indeed, a situation with both a N–S masonry wall as the eastern limit of Room 35, still removed later by the cutting of ditch 5004, and a wooden gate along the southern side of Room 34 cannot be excluded.

A unique feature to Room 35 is the doorway that was cut through the portico wall [5007] in the NW corner of the room. This passage connected the space to Room 4, which also bears evidence of reoccupation (Fig. 11). The doorway was cut from one of the preexisting breaks in the wall caused by the earth movement in the fifth century. Part of the elevation west of the break was removed and cleared down to the level of the bipedal course above the foundations. As the occupation level of Room 35 was ca. 30 cm below the level of the foundations of [5007], there remained a sort of step between the two rooms.

The eastern wall of Room 4 was evident only in the foundations, since they were later cut by 5004, and the northern wall [5059]=[5037] was the original northern wall of the room and of the south block of the barracks as a whole. The western wall [5323] remains in much of its original opus listatum elevation, despite a large scar across most of its interior face. The destruction fill within an apparently original door was not excavated, but a deposit of rubble and yellowish clay (5338) was found in front of the blocked door (Fig. 12). The origins and original purpose of the yellow clay remain unknown.

The surface of reoccupation 5343 within Room 4 was a compact red clay on which several vessels were grouped in the SW corner. A broken quern lay just to the east of them, propped up along the wall. To the north were numerous dolium fragments (5354) in a cut 5444 that had housed the complete vessel. Other noteworthy finds included numerous fragments of metal and a large lead weight (O772) (Fig. 13; Fig. 14). This surface and its components overlay an earlier surface 5355 on which two hearths were found: (5365), a small, round area of charcoal and (5344), a large patch of burned clay with brick fragments embedded in its surface. The clay of this floor resembles that used in the floors during the original occupation elsewhere, but since this surface was not excavated we are unsure whether it dates to that period.

![Figure 16. Detail of [5426] during excavation showing fragment of a granite column shaft reused as building material for western wall of Room 36.](http://archaeologydata.brown.edu/villamagna/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/fig.-15-granite-column-150x150.jpg)

Figure 16. Detail of [5426] during excavation showing fragment of a granite column shaft reused as building material for western wall of Room 36.

Figure 15. Cut to remove a dolium in Room 36 with Room 35 visible at a lower level in the background.

Additional traces of reuse and reoccupation along the length of the portico (Room 36) were evident farther west and uphill from the two-room unit of Room 35 and Room 4. A dolium (5429) was inserted into the surface 5419 just west of wall [5321], though it was removed before the final burning of the reoccupation (Fig. 15). The section of the cut revealed a layer of irregularly laid stones (5443) ca. 5 cm thick well below the beaten earth surface. Because it was not fully excavated, however, the phase of occupation to which it belongs remains unknown. Fragments of a pavement 5418 were found next to the dolium. A clear cut down into the surface of [5022] as well as several reused and reconfigured paving stones placed along its course strongly suggest that wall [5010], which was intended to serve as the southern limit for this space, was constructed along this section of the portico, as well, but a coherent elevation for it was not discernible among the destruction. Though Room 3 north of this area in the portico was not excavated, it seems possible that the two areas were connected in the way that Room 35 and Room 4 were. A gap in the portico wall fronted by a paving stone placed in the surface suggests the presence of a door and threshold, but this reconstruction remains speculative.

Near the western limit of excavation, a concentration of reused building materials (5426), including the lower half of a black granite column shaft, was found stretching between pier [5213] and the northern portico wall (Fig. 16). Abutting the portico wall was a small area of masonry, from which the shaft appears to have fallen. Although the eastern limit of cut 5175 has obscured the western extent of the materials, it is very likely that these comprised another wall built across the portico.

Southern Block

Deposits of the 6th and 7th centuries were also found within the northern rooms of the southern block of the barracks, Rooms 5, 6, 7 and 8. None of these rooms, however, showed the level of structural intervention that was evident in the portico and Room 4, but any newly constructed walls may have been removed by the significant amount of ploughing that was evident across the eastern area of the main structure. The precise nature of the reoccupation in this area therefore remains somewhat elusive, but the presence of material in rooms that appear to have had no access to the reoccupation in the portico suggests that these rooms were at least somewhat still intact and accessible to the sixth- and seventh-century occupants.

Room 5

The SW corner of Room 5 was subsequently cut by the ditch 5004, leaving only partial foundations for its western wall [5018], as already noted in the discussion of Room 4. The northern wall [5037] was here only preserved in partial foundations, and only the lowest mortar bed of the elevation remained from the eastern wall [5044]. Both of these had been ploughed down to these levels.

Figure 18. Pit 5096 in the northwestern corner of Room 5 that contained several fragments of cookware.

Preserved just below the level of the ploughing and overlying a surface of reddish-brown clay or beaten earth 5045 that contained pottery from the sixth or seventh century was a large patch of cement (5046) in the center of the room, with smaller fragments of the same surface surviving around it (Fig. 17). In the NW corner, a roughly round cut 5096, later itself cut by 5004, was found with a fill of ashes (5050) that contained cookware of a 6th century date (Fig. 18). Oak, elm and hornbeam were all identified among the sampled charcoal. This apparent hearth appeared to have been cut into a separate concentration of destruction (5084) that was evident in the northern area. This destruction was evidently the destruction of the original building, left in place likely as a leveling course for the new floor 5045, which has since been ploughed away in this area of the room. This destruction indeed covered the lower beaten earth surface 5106, in which the dolium and other cuts from the original occupation phase were evident.

Figure 19. Reoccupied surface of Room 6 facing south and showing hearth 5113 in northwestern corner.

Room 6

The evidence for reoccupation in Room 6 presented a similar situation to that of Room 5. All four wall of the room had been ploughed down into the foundations, and a brown clay surface 5036 spread across the room in a thin layer, though it had sunk into a depression in the SW corner where the dolium had been robbed out earlier. In the NW corner, another depression contained indications of a hearth where an iron brazier (O418) surrounded by a significant concentration of ash and charcoal (5113) were found (Fig. 19). Oak was identified among the charcoal, but other pieces in the sample could not be identified. As in Room 5, a thin new surface of reddish-brown beaten earth was laid over the earlier floors, which had been cleared of their original destruction, and a hearth was placed in the NE corner.

Room 7

The reoccupation of Room 7 left more evidence than in the other rooms, but the situation here was more complex. Only the eastern wall [5043] survived to any point above the foundations, but the three courses seen in this wall had actually separated from the foundations and had been badly damaged. A piece of cocciopesto reused as a pavement or working surface lay in the center of the room, similar in effect to the preserved pavement seen in the center of Room 5.

There were numerous cuts in the occupation surface 5122 (Fig. 20). In the SE corner, there was a rectangular cut 5134 running along the eastern wall [5043], and several fragments of mixed reused materials were packed in the corner between the elevation of the eastern wall and the and foundation of the southern wall. The purpose of the pit is unknown, but the materials packed into the corner may have been an effort to help stabilize the badly damaged eastern wall [5043], which had been completely separated from its foundations at this location. Within the fill (5138), which dates to the 6th or 7th century, charred barley was also found.

Farther west along the southern wall [5007] was a round cut 5139 that must represent the removal a vessel once stored in the floor here. Though a coin of Claudius II (Gothicus) was found in the bottom of the cut (C54), the pottery dated to the sixth or seventh century. The presence of this vessel, or at least the cut, seems to eliminate the possibility that Room 7 was connected to the structure built south of it (Room 32) within the portico, and thus it was not analogous to the two-room unit of Rooms 4 and 35 to the west. Furthermore, there is no gap in the south wall to indicate such a relationship.

Near the NE corner, a small, rather shallow cut 5136 was found with cement lining (5169) at the base most likely intended to secure a vessel. The fill above the lining (5135) was rather rich in charcoal and ash, and it seems to have fallen into the cut after the vessel was removed.

Figure 21. Room 7 facing west showing removal of northern wall on right after the excavation of the reoccupied level.

At a point certainly after this vessel was removed, nearly the entire elevation of the northern wall [5037] was removed by cut 5130 to the level of the bipedal course east of the western wall [5033] (Fig. 21). As is apparent also in the southern face of the southern wall [5007], [5033] marks the point in these long E–W walls where the level of the foundations was lowered ca. 40 cm to adjust for the slope.2 The bottom of the resulting robber trench therefore lay some 20–30 cm below the surface of the reoccupation. A small amount of the first mortar bed was left in place above the bipedal brick, and a rather large piece of the masonry (60 x 25 x 15 cm) was either placed or had fallen onto the exposed bipedal course just west of [5033]. On the other side of the room, where the eastern wall [5043] meets [5037], the mortar bed for the bipedal course was also cut away, exposing the upper limits of the foundations and leaving the northern end of [5043], which abutted [5037], exposed (Fig. 32). It is difficult to know why the wall was removed, but it seems to have been done so in the same period when the other vessels of the room were being removed.

Given the good preservation of the hearth on the earlier surface of the room, it seems probable that Room 7 withstood the original destruction and abandonment of the building in the fifth century with its roof or the floor of its second storey intact. Its good preservation likely attracted more occupants and activity to it during the reoccupation, but how well it was preserved relative to the other rooms of the structural complex is unknown.

Room 8

Though much of the area of Room 8 extended beyond the eastern limits of excavation, a small area of its SW corner was excavated. The eastern face of [5043], which had been separated from its foundations and shifted slightly to the west of center, had been cut back to about a third of its width across much of its length, thus exposing the surface of the foundations below it. As the northern wall [5037] had been removed, a new wall [5067] was constructed with a reused paving stone and a large tartara block extending into the section ca. 70 cm to the south of the removed northern wall (Fig. 22).

Within the area of the excavated room south of [5067], there was a large, roundish cut, 5062, evident that had removed part of the eastern half of [5043] and continued into the section. The fill of this cut, (5062) consisted largely of mixed destruction materials. There was, however, a concentration of mortar chunks in the material of the northern half of the fill, which should be identified as the material from the collapsed elevation of [5067].

Road

Since the structure of the barracks was intensely reoccupied, the road to the south of it seems to have remained functional, despite the deformations caused by the fifth-century earth movement. Although the surface had sustained little damage in the eastern side of the trench, it had dipped significantly to the west of where the ditch 5004 would later be cut in, due south of the later Room 4/Room 35 complex. It seems rather clear, however, that efforts were made during the reoccupation to level out this depression in front of the reoccupied unit and, to a lesser extent, across the remainder of the road surface. A compact layer of material (5014) dating to the sixth or seventh century was found mostly between the pavers but sometimes on top of them, and this material covered the small masonry element [5379] protruding from southern face of the southern wall of Room 35 [5320], as well. Two additional deposits were subsequently laid within the sunken area of the road in front of Room 35: an extensive dark, ashy layer (5289), from which a carnelian intaglio bearing imperial iconography (O687) was recovered, followed by a layer of brick fragments (5380), and one of soil and stones (5353). These deposits essentially reached the level of the surrounding undisturbed road surface, and atop these, several paving stones (5378) were then placed along [5320], forming a sort of threshold up into Room 35 (Fig. 23). Above these layers, (5290) forms the final level of material used as a surface over the old road. The construction of Room 35 and the repair of the road thus seem to have been contemporary events, with the dark brown and compact (5290) perhaps a layer laid or built up during the course of the structure’s occupation.

The lowest deposit covering the road (5014) also covered the concrete patches around the gate [5030] in the southeast corner of the trench, suggesting that this structure permanently went out of use with the original destruction of the barracks in the fifth century and was not reconstructed.

Large Rectangular Building

Figure 25. View from north of southeastern corner of the robber cut exposed, but unexcavated, with interior surface 5226 still preserved within it.

Figure 24. Cut 5175 in western section of the trench related to the robbing of the eastern wall of the Large Rectangular Building.

Another large, linear cut 5175 with the same orientation as 5004 became evident in 2007, but when the limits of excavation were expanded to the west and the south both in 2008 and 2009, it became clear that the feature continued and was actually rectangular in shape, with the longer sides on the east and west ca. 16 m long and the shorter north and south sides ca. 6 m long (see Fig. 2). All of the cut that was visible within the trench was excavated except the part in the southern extension of the excavation, where the southern side and SW corner of the feature, enclosing what remained of an interior pavement 5226, were only exposed (Fig. 24; Fig. 25; see also Fig. 2). Material inside the fill (5174) dated mostly to the sixth and seventh centuries.

That the entire cut is a robber trench for the walls of a rectangular structure was apparent from the remains of two cocciopesto basins, [5237] and [5236], oriented parallel to the long sides of the feature and separated by a small space, perhaps once a channel or wooden barrier, ca. 30 cm wide. The width of the two basins and the space between them occupy together the entire six meters of northern side of the cut (see Fig. 2). They were constructed on foundations 40–70 cm high, comprised of large stones and mortar without any discernible face. These must have been built against a structure removed by the cut at its north end (Fig. 26; Fig. 27). On the southern side, the foundations of the basins were constructed over and against fragments of wall [5220] from the original structure of the barracks. Unlike the ditch 5004, the robber cut around the basins left in place several fragments of the intersected original E–W walls, as well as almost all of the latest pavement in the corridor, 5401, which consisted of numerous reused fragments of marble. The wall as built must have simply incorporated these elements and sat almost immediately on top of the corridor pavement.

The function of the basins and the rectangular structure as a whole is difficult to determine with certainty. The western basin shows a circular area of wear in the center of its northern side, perhaps indicative of a spot where water drained onto it from above, but any evidence of any larger hydraulic system to which it belonged has not survived. Given the clear evidence that wine was being stored in the area of the church and former imperial residence about 100 m to the west, we might interpret these vats and the structure around it as a wine-production or grape-processing facility, interpreting the wear in the vats as the effect of treading the grapes, the step as access and the central drain as the means by which the juice flowed into the rest of the building. The construction technique of the building must have been of a much higher quality than the reoccupied spaces within the barracks.

Room 28 was reoccupied at this time, as well—as sherds of spatheia 3a found there show—probably in relationship with the construction and use of the rectangular building.

Phase VI: Destruction of the reoccupied areas

At an indeterminate later point, though probably no more than a few decades after the reoccupation began, the reoccupied structures were destroyed by a fire. It is unknown if the fire was accidental or intentional, but given the political instability of the area in the sixth and seventh centuries, it does not seem impossible that the fire was the result of hostile action.

Overwhelming evidence for an extensive fire throughout the entire structure was found within every reoccupied space. Clearly distinguishable burn layers were recorded throughout the entire length of the portico—(5029) in the east and (5300) in the west—and also within Room 7 (5119). Under the burn layer of the portico, numerous linear concentrations of charcoal were found on the occupation surfaces of each space. These were particularly clear in Room 32 in the east, where the burnt remains of planks or beams (5060) running parallel to the portico were easily distinguishable (Fig. 28; Fig. 29); these elements may have been roof joists or something similar to shelves or benches inside the room, but the recovery in the northern area of the room of two nearly complete jars aligned and approximately 1 m apart immediately below the charcoal suggests that the latter function is more likely. Indeed, the orientation of the charcoal parallel to the portico seems to exclude them as roof or ceiling joists, which would be oriented perpendicularly to the space. Other similar concentrations of charcoal were found beneath (5300) in Room 34 and in the western area of the portico in Rooms 35 and 36 (see Fig. 10). Analysis of samples showed that all the wooden elements discernible within the portico were of oak.3

The burn layer (5119) within Room 7 resembled that of the portico, but it contained an extraordinary amount of ceramics, mostly cookware, dating to the sixth or seventh centuries and including several nearly intact vessels (5121) sitting on the beaten earth surface 5122 below it (Fig. 30). Patches of charcoal, rather than linear features, were variously located within the room, and samples identified the species of wood as oak here as well.

No consistent burn layers were found in Room 5 or Room 6, but a marked quantity of charcoal was found mixed within the materials of the destruction layers overlying the surfaces of each room. The wood was identified as oak in these locations, as well.

Concomitant with the burning of the building, the reoccupied structures either collapsed or were razed, as evident in the extensive destruction layers that overlay the burn layers. These were all uniform in their composition, if not in their state of preservation. Consisting of mixed building materials, such as a stones, bricks, tiles, pieces of mortar, charcoal and ceramics dating to ca. 530–650, the deposits were generally deeper in the east than in the west, but they varied considerably because of the irregularities of the slope and the modern ploughing, which has penetrated ca. 50 cm below the surface. In addition to the other evidence, the generally large quantity of material also seems to indicate that much of the original structure had survived the damage suffered in the fifth century and that the reoccupation exploited the remains. Fragments of bonded masonry courses consistent with the masonry of portico wall [5007]/[5008] were evident in the destruction layers of Rooms 5 and 7, particularly in the southern half of each room, indicating with certainty that this wall remained largely intact in its original form before the final destruction.

The destruction material within Rooms 5 and 6 was less preserved due to the ploughing, which had penetrated into the reoccupation surface in certain areas of the rooms. While most of the destruction within Room 5 (5084) had been ploughed away, some material had survived in the western half of Room 6 (5035), from which a Justinianic coin (C64) was recovered.

The destruction within the eastern area of the portico (5002), Room 7 (5034) and Room 8 (5062) were particularly deep, up to 50 cm, despite the ploughing that had undoubtedly removed some of it, as evident by the marks that had gouged the top of both layers. This destruction material helped to preserve the burnt wooden elements that were particularly distinguishable here. Likewise, the features of the final occupation surface of Room 4 were well preserved because of the thick destruction (5312) and (5329) atop them; and the particularly steep slope at this point and the survival of most of the room’s western wall also protected it from the ploughing.

The destruction material that spread across the road presents no significant variations, though a deposit of clay with stones (5377) that had clearly collapsed from the front, southern wall of Room 35 was distinguishable under the much broader destruction (5005) that spread across much of the southern part of the trench. Room 17 was also implicated in the destruction, as evident by the deep deposit of destruction material (5201) datable to the same period here.

At some point after the destruction of the reoccupation across the structure, an infant was buried (5123*) in a simple grave cut along the western wall [5033] (Fig. 31). Unlike the earlier infant burials found in the northern rows across the corridor, this burial was not carefully placed flush against the wall, but rather slightly oblique from it, oriented NW–SE, nor was it laid upon any kind of base, such as the reused tiles or marble slabs seen in the earlier burials. The grave was also very shallow, and the destruction material that had fallen above it had obscured the limits of the grave cut around it.

Phase VII: Cutting of the ditch

Figure 32. Plan of the ditch 5004 carved across the slope after the destruction of the reoccupied areas and the Large Rectangular Building (Margaret Andrews).

After the burning and destruction of the reoccupation in the early- to mid-seventh century, there was a significant intervention in the area which took the form of a large, distinct linear feature 5004 cutting SE–NW through the center of the trench (Fig. 32; Fig. 33). Resembling a ditch, the feature runs N–S through the entire width of the trench. It was clearly distinguishable from the destruction material around it by its looser, darker fill (5005). The ditch is flat in the bottom, but U-shaped as it transitions to the irregularly shaped sides. Walls and their foundations that were intersected by the cut were simply cut through, showing clearly the form of the ditch in section. The cut was typically 1.75–2 m wide and 50–80 cm deep, at least from the level of the destruction preserved after the modern ploughing; its original depth is therefore unknown. The material from the ditch appears to have been cast up on its west side, where the destruction deposit is notably thicker. This would have increased the height of the barrier on that side.

The orientation of the feature does not respect or relate in any meaningful way to the orientation of the earlier structure of the barracks, but it is important to note that its course coincides with the line of uplift in the slope of the hill presumably caused by the local earth movement in the fifth century. Cutting the ditch along this path would have been considerably easier considering the broken walls and looser material. Indeed, much of this fragmented material may have been removed already during the reoccupation, making this line along the slope even more suitable for the situation of the ditch. What purpose this large cut may have served is unclear; though it could represent a robber trench for a wall, it seems more likely to have served defensive purposes.

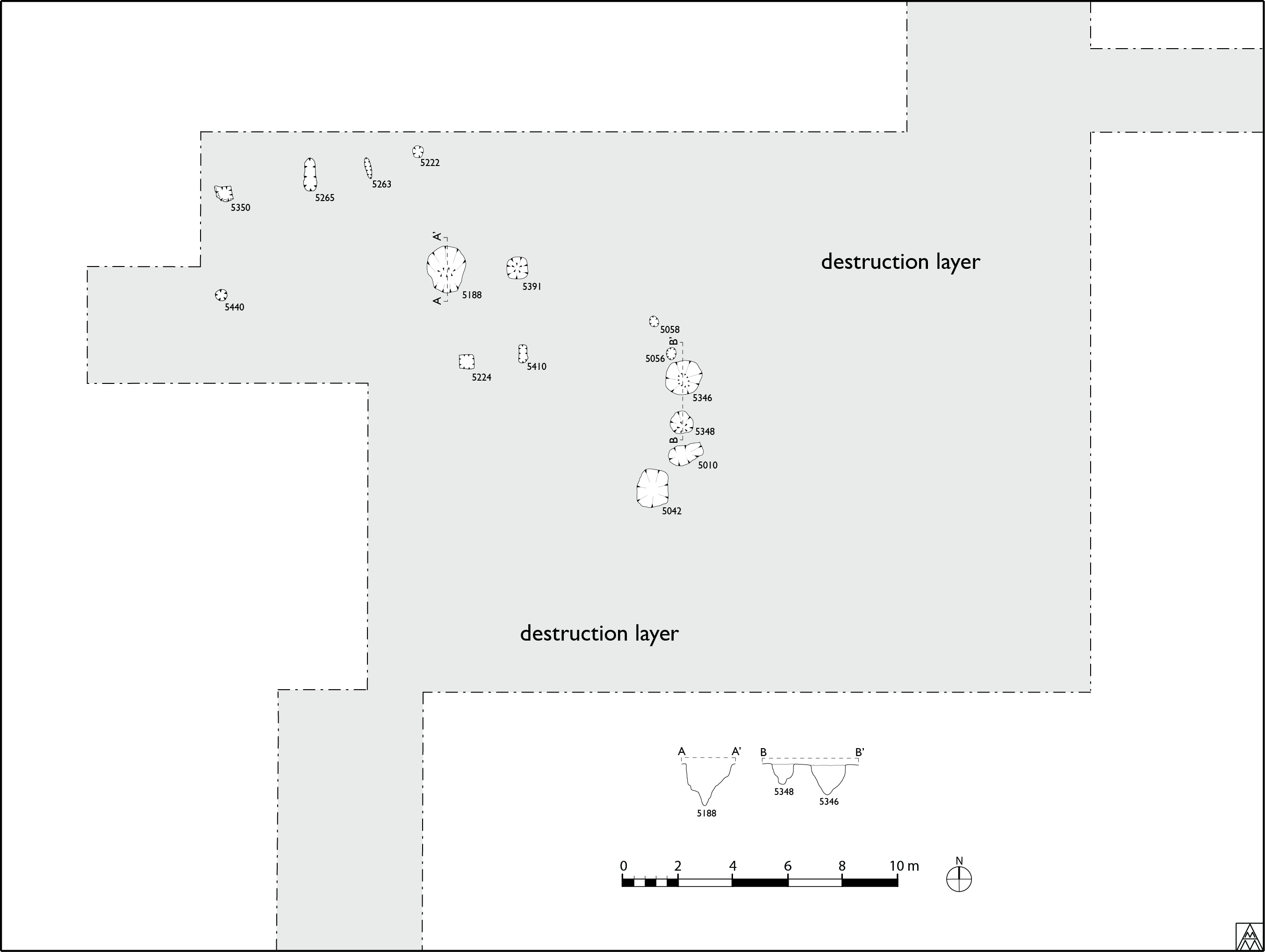

Phase VIII: Structures built with wooden posts

At some point in the middle of the seventh century, the ditch was filled and a series of postholes was cut: 5010/(5009), 5042/(5041), 5056/(5055), 5058/(5057), 5188/(5187), 5222/(5223), 5224/(5225), 5263/(5262), 5265/(5264), 5346/(5345), 5348/(5347), 5350/(5349), 5391/(5390), 5410/(5409) and 5440/(5439)(Fig. 34). All datable pottery from the fills yielded dates in the sixth and/or seventh centuries.

Eleven of the fifteen holes were cut into or against E–W walls original to the barracks. Holes 5350, 5265, 5263 and 5222 relate to [5239]; 5440, 5188, 5391 relate to [5209]. Postholes 5224 and 5410 were cut into [5210], while 5058 and 5056 are cut up against the northern and southern sides, respectively, of the same wall. Postholes 5348 and 5010 likewise flank wall [5007]. Though the holes apparently cut within the width of the walls could simply represent cracks where loose material fell into the void, the very deliberate forms of the holes indicate that they were purposefully dug. Moreover, the frequency with which the holes correspond to walls of the barracks is significant enough to suggest that their relationship was not accidental. Indeed, the locations of these walls would have been evident both in the section of the ditch 5004 before it was filled in with (5003), and when the robbing of the walls around the large rectangular building was carried out.

The holes are of various forms and depths. 5188, 5346, 5348 and 5391 were clearly broader in the upper parts of the hole, with a clear narrowing near the bottom to receive the post securely (Fig. 35). Other holes—namely 5056, 5058, 5222, 5350 and 5440—seemed only to show a uniform narrowness through their entire depth, while still other holes, such as 5010 and 5042, showed no noticeable narrowing. The depth of the holes also varies, ranging from 30 cm to 1.6 m.

The arrangement of the holes collectively in plan perhaps shows two separate structures, both with a rounded end on its down-sloping eastern end. Postholes 5350, 5265, 5263 and 5222 likely constitute the southern side of a structure that just barely begins to curve toward the north towards a rounded end that would lie beyond the northern limit of excavation. The remaining holes could all pertain to a single, rather large apsidal structure, with 5410 and 5224 serving as internal supports or otherwise representing holes that served a completely different function inside the structure. At the very least, the spatial relationship between 5348, 5010 and 5042 indicates that these all must have belonged to a single structure.

Since 5056, 5058 and 5346 all cut the fill (5003) of ditch 5004, and 5440 cuts the fill of the robber trench (5174) and can reasonably be associated with the other postholes to the east by virtue of their alignment, we can safely assert that the cutting of the postholes post-dates the life of the defensive features.

Phase IX: Indeterminate medieval activity during the castrum period

A small excavation carried out in January 2012 revealed a medieval occupation layer (5500) to the west of the large basins and apparently extending over the fill of robber cut 5175. The function of the layer, which consisted of a relatively compact soil, is ambiguous, however, as its surface was irregular enough to doubt its function as a constructed surface. A large quantity of pottery that yielded dates primarily in the early fourteenth century was recovered, and therefore contemporary with the ‘castrum’ phase of the monastery uphill to the west.4 The nature of the occupation here is unknown; it was certainly in use, but perhaps only as a marginal space, not a residential or productive one.

1 On the construction strategy for the barracks see: Andrews, print volume: 125–8.

2 See: Andrews, print volume: 125–8.

3 See: The Plant and Animal Remains

4 On the features of the castrum phase at the monastery, see: Goodson, print volume: 335–40); on the associated pottery, see: Rascaglia, print volume: 341–7.

![Figure 9. Detail of [5321], the western wall of Room 35.](http://archaeologydata.brown.edu/villamagna/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/fig.-08-western-wall-room-35-150x150.jpg)

![Figure 8. Detail of [5022], the southern wall of Room 35.](http://archaeologydata.brown.edu/villamagna/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/fig.-07-south-wall-room-35-numbered-150x150.jpg)

![Figure 22. Newly constructed northern wall [5067] of Room 8.](http://archaeologydata.brown.edu/villamagna/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/fig.-21-room-8-wall--150x150.jpg)

![Figure 27. Vats [5237] and [5236] from north, showing their foundations.](http://archaeologydata.brown.edu/villamagna/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/fig.-26-numbered-150x150.jpg)

![Figure 26. Upper surface of vats [5237] and [5236] from south.](http://archaeologydata.brown.edu/villamagna/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/fig.-25-basins-numbered-150x150.jpg)