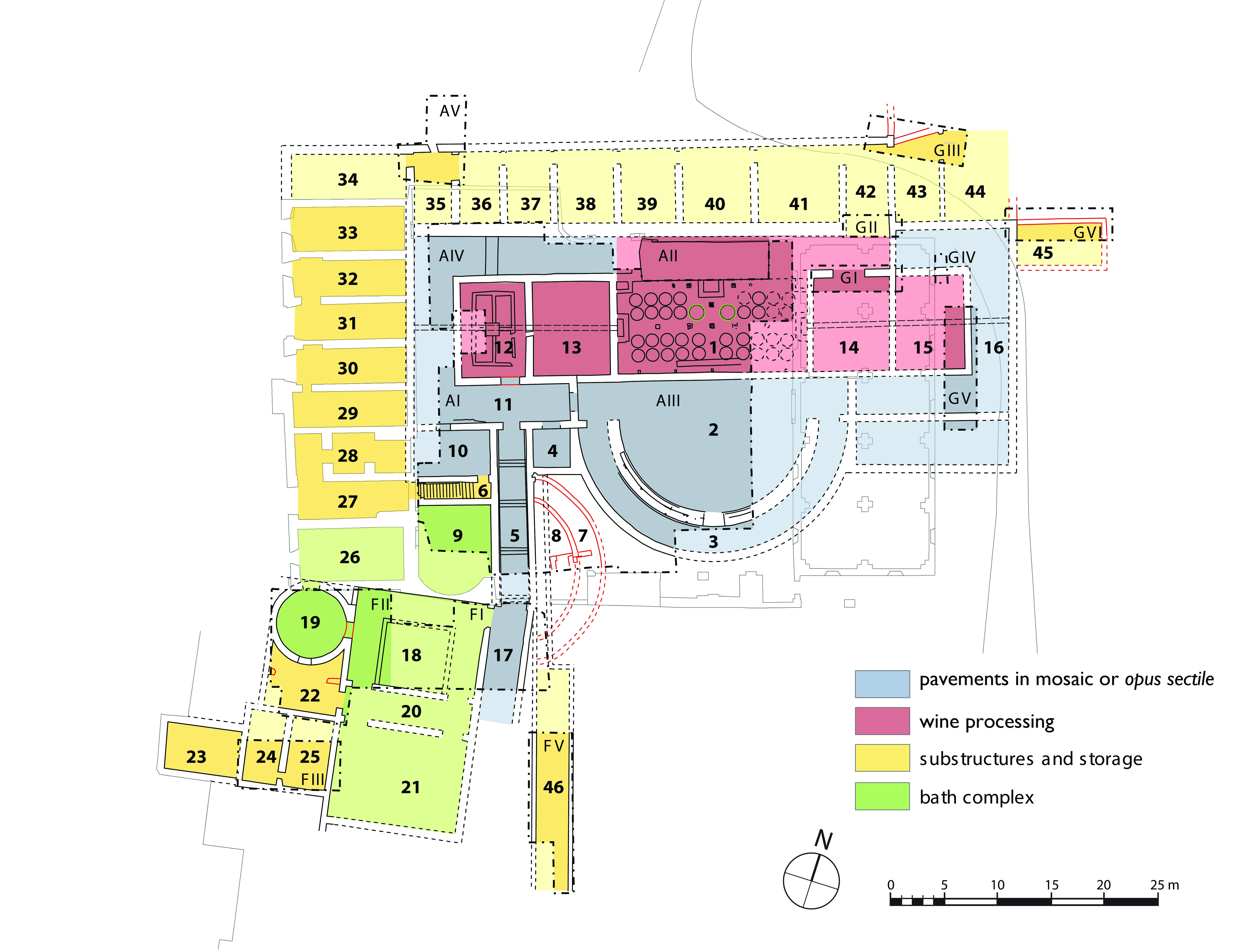

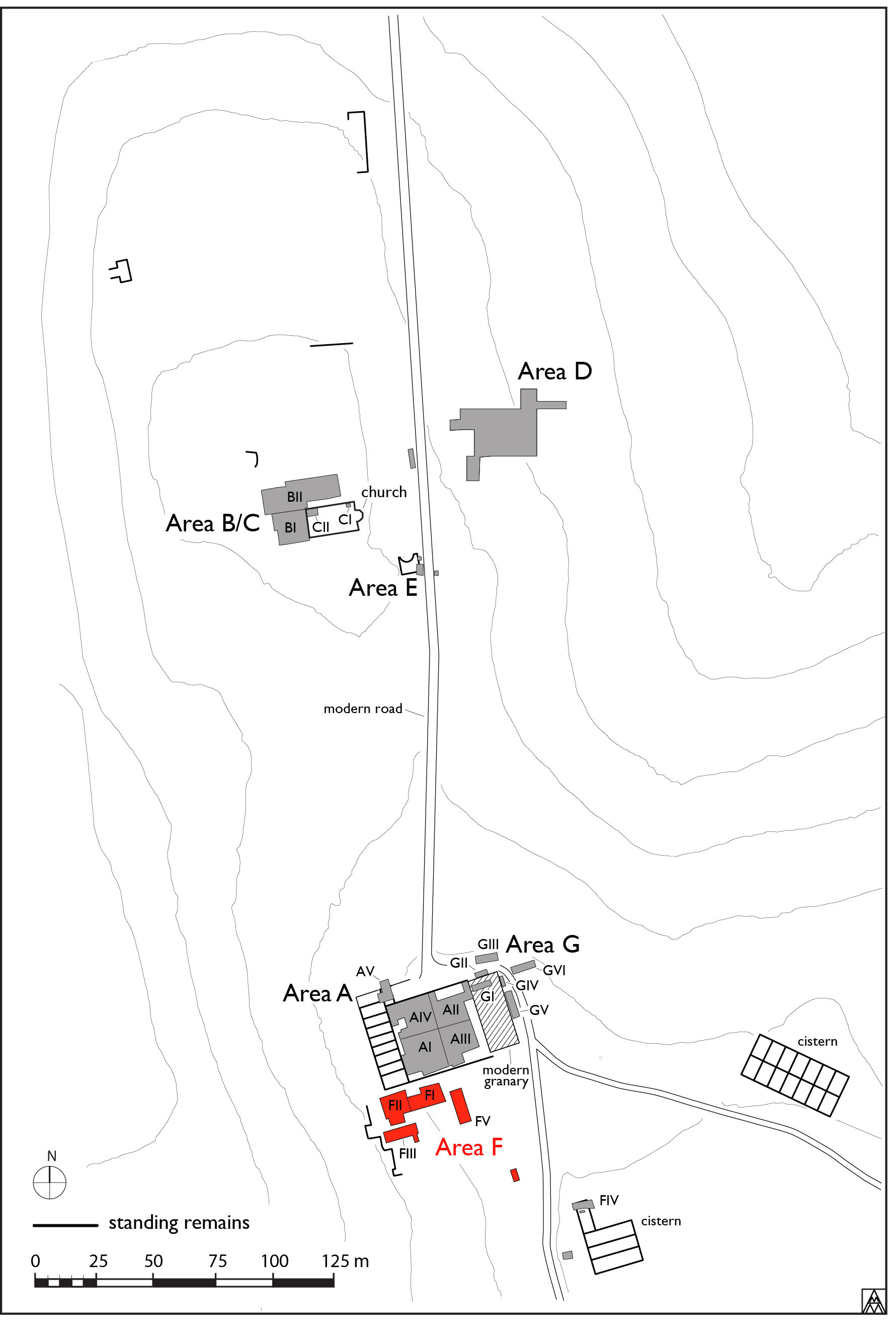

All of the Roman structures excavated to the south of the winery seem, because of their orientation, to form part of a very separate building, interrupting the perfect axial plan of the main structure (Figs. 1–3). The corridor and the monumental staircase serve as a connection between these two units, which, notwithstanding their different orientations, are clearly of one build and functional in the general scheme of this imperial villa. This section treats the stratigraphic sequence of this earliest phase of trenches FI–III, the winery baths. It seems logical to treat them separately from the winery in view of their very different function and because the stratigraphic sequences cannot be related. In fact, the stratigraphy of this area was far better preserved than that inside the casale, where later interventions removed almost all of it. The post-Roman phases of this area, which run from the ninth through the thirteenth century, are described in both the print publication and by Darian Totten in the associated stratigraphic report for this area in later periods.1

The excavation of this part of Area A, which was empty of structures apart from a terrace wall forming part of a large garden, began in 2008 with the opening of two adjacent trenches, FI and FII, along the southern side of the casale, supervised respectively by Darian Totten and Dirk Booms (Fig. 4). The two excavations were continued in the next year, when a third trench, FIII, was opened a few metres to the south in order to identify the structures in that direction. Additionally, a long, shallow sondage concentrating on the wall [7505]=[12001], which lay just under humus, was created to establish the limits of the building.

The entrance corridor

Room 17

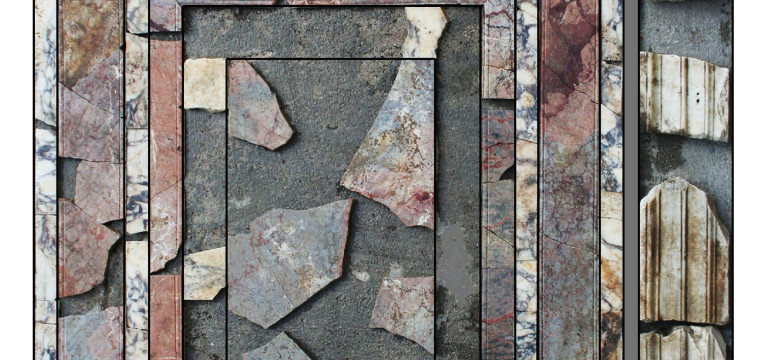

As we have seen, the southern part of the structure is linked to the winery by a monumental, stair, Room 5. The corridor, Room 17, meets the door between the two at an angle of 10°, but the bond between them is very clear. The corridor was paved with a white mosaic identical to that of the stair 8143 and the opus mixtum construction of the walls, [8011] on the west side and [8013] on the east matched, as well (Fig. 5). The paneled veneers of the walls rose over a low dado of portasanta marble from which they were separated by a moulding in white marble (Fig. 6). The veneers had collapsed onto the pavement, detached from the thick layer of mortar that originally held them. They lay in a layer with wall plaster, which must have come from a higher level, as well as iron pins for the veneers in portasanta, giallo antico, porphyry and luna marble (8137). The imprints of the veneers on the mortar allowed the reconstruction of the paneling (Fig. 7). Immediately south of the door into the stair was a second door, leading into Room 18, the atrium, to the west. The door was framed with an elaborate cornice of white marble. A step framed in marble led up towards the atrium.

The atrium

Room 18

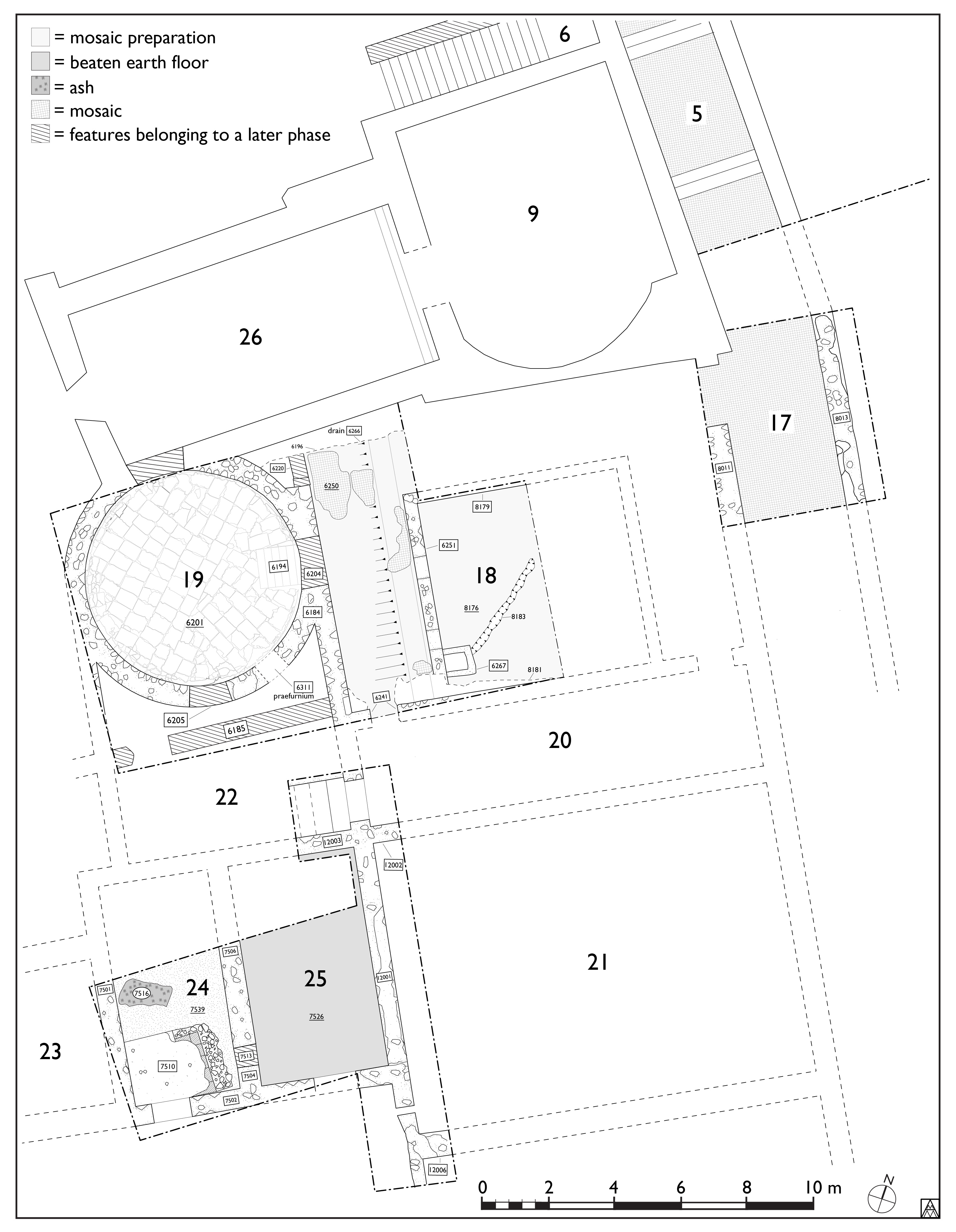

After preliminary cleaning, only the western half of this room was excavated, although it appears to have been symmetrical along a north–south axis (Fig. 8). The plan of the room appears to have been an open central space surrounded by a portico on its western, northern and eastern sides. The floor of the portico, in white mosaic, 6250 on a cement preparation, 6217, was some 34 cm higher than that of the open space and the surrounding corridor, which was also paved in mosaic. A large cut in the north end of the portico, 6196/(6197), showed that the preparation was formed of two layers of cement, separated by a lens of yellow clay (6236). It also revealed a large drain, [6266], covered with tiles placed a cappuccina, running north–south along its entire length.

The covered space of this corridor was delimited on its east side by a low wall, [6251] which continued in the northern section of the trench, [8179]. 14 cm high and framed with white marble veneers (6272, 6310), the wall formed the stylobate for four columns or square piers on each side, which supported the roof. Traces of these are still visible on its surface (Fig. 9).

The southern limit of the portico is visible in the south section of the trench. This was a wall in opus mixtum, [6241], also covered with a marble veneer, as indicated by a few fragments and, above all, small holes for the cramps that held the marble, 6273, of which a few fragments were preserved. A door at the west end of this wall with a threshold still in place [6290], subsequently blocked, [6252], opened onto a corridor to the south of the room (Fig. 10). The stylobate is interrupted at this point by what appears to be an opening into the centre of the court. South of this opening, and in line with the stylobate, two small holes of identical size, one above the other, suggest the presence of a pilaster which would have echoed those of the portico and framed the side of the door.

The open court was paved with a layer of opus signinum, 8176 over which a thin layer of mortar held a mosaic pavement, 8178 preserved in only a few fragments but apparently identical to that in the corridor around it. In the southeast corner of the space was found a square structure lined with bricks, [6267, 6266] which appears to have been the main opening for a drain which probably connected to the long drain in the corridor of the portico.

Two further cuts were visible in the pavement, one running along wall [6241] and a second in the centre of the room, from the door in the southwest corner to the centre. The first, 8181, was 40 cm deep and 30 cm wide; it almost certainly represents the robbing of a lead fistula. The second, 8183, was also a fistula whose course remains visible in the pavement. The presence of the larger drain in the corner of the room, and the fact that this fistula stops in the middle of the room, suggests that it brought water from outside towards the centre of the room, which was probably ornamented with a small fountain operated with the valve found precisely at the end of the cut (Fig. 11). The opus signinum preparation for the mosaic seems to indicate that the water flowed from the fountain over the whole area, adding sparkle to the light in the room. Its position in the exact centre of the space between the east and west sides of the room allows us to reconstruct a symmetrical plan, with three wings of the portico around the central space. The whole room thus forms an atrium, or distribution space.

Room 19

Just west of this room, separated it by a common wall, [6184], is a round room 6.40 m in diameter. This was entirely excavated, apart from a small portion of its south wall that has been subsumed by the modern north wall of the casale (Figs. 12 and 13). The wall was again in opus mixtum with vittatum quoining. It was, however, built on a brick foundation, which continues for 98 cm above the surviving pavement. Holes for cramps for a marble veneer are found in the upper portions of the wall. There are four apertures in the wall. Three of these are doors at the level of the floor of Room 18: one to the east, leading into Room 18, one to the south, and one to the north, into Room 26. These have all been blocked: the eastern door by [6204] (Fig. 14) and the southern one by [6205]. A fourth opening, on the south side, is framed in sesquipdales [6311]. Measuring 30 cm wide, it is missing its arched top, of which only the springing is visible. This was certainly the opening of the praefurnium, which would have brought hot air into the room. The paving of the room, 6201, is certainly secondary, formed of bipedales set into a preparation of cement. Along the line of the praefurnium, a patch in the floor is evident. This pavement is covered by a layer of plaster fallen from the walls (6200); some of this is preserved on the walls themselves, and forms a half-round moulding at the base, demonstrating some secondary use for the structure, a use confirmed by the find of an illegible graffito at a low level. However, the structural characteristics of the room, the praefurnium and the low level of the floor compared to the door, certainly indicate that it was originally intended as a hot room for a bath complex, a tepidarium or heliocaminus. The lack of tubuli along the walls must depend on the later refashioning of the room, when a stair, [6194], covered with the same tiles, linked the lower floor level to Room 18. Although there is no trace of the pilae which would have supported the hypocaust floor, some were found in the destruction layer, (6191) which, followe by (6189) and (6190) formed after the collapse of the building.

Room 26

This room, oriented, like Room 9, along the same orientation as the winery, measures 10.20 x 4.90 m and was entered through a door in the south wall of Room 19. More than this we cannot say: a modern wall on the east end made it impossible to see the relationship between this room and Room 9 immediately to the east of it. It was certainly a hot room, however, whose praefurnia were in all probability found to the west, where a modern cut and rebuilding has removed any trace of the older wall.

Room 9

This room is almost square, measuring 6.17 m north–south by 6.24 m east–west, and it terminates on the south side with a shallow apse, 1.5 m deep. Its excavation was complicated by the great depth of the deposit and the necessity of leaving the modern fountain inside the apse intact. The upper levels of the room were filled with a relatively clean clay (1502) to a depth of almost 2 m below contemporary ground, the removal of which revealed a small vat, [1500], measuring 1.21 m x 1.47 m, abutting the Roman stair, Room 5. At the base of this clay were splashes of lime, which covered much of the area, and traces of burning (Fig. 15). We interpreted the whole as an area for processing lime. The lack of a kiln makes this somewhat problematic, but the vat itself, with its dense deposits of lime, was certainly used for slaking; the lime deposits must relate to the construction of the modern casale. Below them, mixed earth and stones showed no trace of a pavement. The excavation was abandoned for reasons of safety at a depth of -4.1 m, in correspondence with a foundation offset in wall [1070] on the east side of the room. This height corresponds to that of the pavement of the portico in Room 18. We may assume that the absence of the pavement was due to the fact that here, too, it was the upper level of a hypocaust floor.

Access to the room could only have been through Room 26, in that neither the stair, nor he north and south walls have any signs of an opening. It is possible that the apse served as the position for a labrum; certainly it would have been the source of any light in the room, whose shape suggests a calidarium. Rooms 19, 26 and 9 thus form the circuit of the hot rooms.

The service rooms

Rooms 22–25 are part of the service rooms of the baths. These were excavated in Trench FIII, to the south of Room 19, along the line of wall [6184] which divides Rooms 18 and 19, and forms a key boundary within the baths as a whole (see Fig. 3).

Room 22

Just south of the atrium, wall [7501], the continuation of [6184] is interrupted by a door leading into Room 22. This door opened onto a stair leading downwards, of which only the top step was revealed. This is delimited to the south by an east–west wall in brick, [12003] bonded to [12001]=[6184]. Just beyond the first step, the presence of a lintel arch formed of bipedales is visible in the wall for a metre. The wall itself was topped by a cement pavement, 12005, which reappeared over the same wall 2 m to the west.

Although we were unable to dig to a lower level, the presence of this brick lintel arch suggests a door in the lower portion of the wall that would have led into Room 25 at the base of the stair. 12005 would have represented the ceiling of the room, pierced to allow the passage of the stair. Over Room 25 was found a fragment of the same paving, probably supported by a vault, 12004.2 The north wall of this room contained the opening of the praefurnium mentioned above, so the room must have contained the furnace which heated Room 19, placed to the north of the stair. In a later phase, an east–west wall [6185] was built between the stair and Room 19, effectively eliminating the probable furnace.

Room 24

Rooms 24 and 25 form a rectangular space delimited by the north–south wall [12001]=[7505] to the west, [12003] to the north, [7501]=[12001] to the east and [7502]=[12007] to the south (Fig. 16). The rooms were divided by a wall in opus mixtum with opus vittatum quoining, [7506]=[7504] which abutted the external walls, but which seems to have been built at roughly the same time. A door in this wall put the two rooms in communication. Room 24 was completely filled with a destruction level including fragments of its vault, (7508), with a substantial admixture of modern rubble at the upper levels probably deriving from the construction of the casale.3 In the southwest corner of the room was built a high plinth, [7510], measuring 2.81 x 2.16 m and built of bricks and mortar. At the base on the north and east sides of the structure was a line of tiles set in a cement preparation (Fig. 17). Immediately above this plinth was an opening in the south wall which served either as a window or, more likely, a passage for a fistula bringing water into the baths. Indeed, the best interpretation for this structure is a support for a small cistern which would have fed the hot rooms of the baths. The rest of the floor was of cement, 7539, covered in the north half of the room by a series of layers in which dumps of ash, (7516), (7531), (7532) were interleaved with layers of ashy clay (7536), (7538). These may have derived from the rake-out from the furnace in the next room.

Room 25

The room to the east of this was filled with a silty dump of medieval material, which probably accumulated over time. This formed over a beaten earth surface, 7526, created in conjunction with the blocking of the door into Room 25, [7513]. The south wall of the room was cut by a large pit which did not, however, continue into the room (Fig. 18). This room was certainly covered by a vault, whose flat surface, [7507], is preserved on the east side of the room (Fig. 19). This must relate to the fragments of paving already mentioned next to the stair, 12004 and 12005, as they seem to show that the whole area had similar ceilings and—rather more importantly—that it was open to the sky.

Room 23

The final room in this set, Room 23, to the west of Room 24, is the only one entirely preserved. It too is covered by a low vault and is filled with earth. Its size and its lack of connection with Room 24 makes its use uncertain, especially as we were not able to excavate it. However, it may have opened onto Room 22 on its north side and could perhaps have been used as a wood store for the furnace.

The cold rooms: Rooms 20 and 21

The area to the east of [12001] was not excavated, so our only evidence for this area is the line of the wall itself and two small returns toward the east, [12002] and [12006]. The first of these defines the southern edge of what must have been a corridor, Room 20, running south of the atrium, taking the place of the portico on that side. It may have led out into the corridor at its west end, and served as another entrance to the complex. In that position, it might be interpreted as an apodyterium.

To the south of there seems to have been a large room, measuring 11.5 x 9 m, Room 21. We would suggest that it was the frigidarium of the baths, although this must remain a hypothesis.

Reconstruction of the baths

Figure 20 gives our conjectural suggestion as to the plan of the whole complex. We propose that the bathers entered through the corridor, Room 20, where they would have disrobed. They would then have moved through the atrium Room 18 into the heliocaminus/tepidarium Room 19, from which they could have stepped outside to the terrace over the service rooms to sunbathe and admire the view. Once warmed up, they would move into the two calidaria, finishing in Room 9. The return would have been retrograde, as there does not appear to have been any connection between Room 9 and the atrium, although a door at that point would have been logical. From the atrium, then, they would have moved into the frigidarium, Room 20. Bathed and dressed, they would have returned to the corridor to mount the imperial stair into the winery.

1 For full discussion of the post-Roman village, see: C. Goodson, print volume: 265–70; D.M. Totten, print volume: 302–14.

2 The cement levels recognised are at a level which is significantly higher than the level of the mosaic floor in the corridor and the two thresholds of walls [6241] and [6204]=[12001]. Thus the rooms were surely at a different level. The discovery of 2 subterranean rooms to the south of these structures confirms this hypothesis.

3 The current proprieter remembers that his father used a mechanical backhoe in the 1950s–60s to cover and level out the ancient structures which are now partially visible in this area of the casale.

![Figure 15. The plinth [7510] in the southwest corner of room 24.](http://archaeologydata.brown.edu/villamagna/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/16.-the-plinth-7510-in-the-southwest-corner-of-room-24-150x150.jpg)

![Figure 16. The south wall of Room 25, [7502].](http://archaeologydata.brown.edu/villamagna/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/17.-The-south-wall-of-room-257502.-150x150.jpg)